It Follows delivers horror with depth

It Follows is a tight script that deftly weaves character, plot, and theme with supernatural elements without sacrificing realism. This is rare for a horror screenplay that often trade on effects, jump scares, and dramatic twists to keep audiences interested. As all great horror and sci-fi does, It Follows taps into cultural anxieties to disturb and delight audiences, but it goes farther to comment on horror, our ideas around sex and growing up. David Robert Mitchell truly captured lightning in a bottle with this screenplay that won the Next Wave Award for best screenplay, among many other awards and nominations.

The film is amongst my favourites of all time and I was pleased to discover that the screenplay was more expansive and filled in some gaps in story and characterization that were obviously cut for reasons of pacing.

It Follows is the story of Jay, a 19-year-old girl who is on the cusp of adulthood but still living at home in the suburbs of Detroit. Her life changes forever when a sexual encounter leaves her with a shapeshifting monster following her everywhere she turns. The obvious subtext here is a not-so-subtle take on the stigma surrounding sex and sexually transmitted diseases. This essay will address that but will go deeper into how It Follows uses effective writing to comment on feminism and the interplay between childhood and adulthood, as well as create compelling characters and effective horror.

Teen slashers hold up virginity as a virtue and make sex a crime punishable by death, It Follows does this even more directly. Having sex with the wrong person curses Jay to a life of being hunted down by a literal monster. The rules of It Follows are simple, and laid out directly via dialogue early on. Jeff (aka Hugh) gives Jay the supernatural STD that I will refer to simply as ‘the monster’, in the first act. He describes the rules as follows:

He also says: the monster is invisible to everyone that has not contracted it, it can shapeshift into anyone (including people you know or even you), it will follow you at a walking pace wherever you go, it is slow but it isn’t dumb (so you shouldn’t go anywhere without two exits). Basically, you can run, but you can’t hide.

This may seem like clumsy exposition but it actually defies the genre in a very important way. Blake Snyder describes a character in every monster movie known as half man: “half man – The partial survivor who has had an interaction with the monster in his past and comes away damaged in some way because of it. This is the “false mentor” who can tell the hero — and us — the horror of what dealing with the monster will entail — and who is sure to die (usually at page 75)!” (Blake Snyder, Save The Cat) Jeff cannot die because, as explained above, the monster will only go back to hunting him once Jay is dead. Another way he differs strongly from the typical “half man” in horror is that he’s fully rational and explains the rules in such a direct way that it removes huge elements of mystery that are typically present in horror. This allows the pure dread of the concept to take over. The first half of the movie is spent with Jay trying to convince her friends that the monster is real. Once they realize that she’s telling the truth, the horror really ramps up as we realize, even if she convinces everyone around her, she has no hope of stopping it. This is a unique take on horror that usually trades on the dramatic irony of the audience knowing the killer is behind the door long before the characters.

There are things that make Jay your typical female horror movie protagonist. Think Laurie in Halloween. She’s young, attractive, pleasant and totally oblivious to the horror she’s about to undergo (at least for our first ten minutes). But instead of merely terrorizing her, the events of the film force her to make decisions that reveal her character. Because she’s given the rules early on, she has agency in how she approaches the problem. She enlists the help of her friends, she tracks down Hugh who infected her to find out the truth, and she faces the difficult decision of whether or not to pass the monster on to someone else.

In addition to having a female lead with agency, This piece can be read as showcasing a lot of feminist/antifeminist ideas. The idea of ‘hysterical women’ is explored in everyone’s refusal to believe Jay about the monster.

Much the way that rape victims are either discounted or pitied or both, Jay is treated as a bit of a basket case by her sisters and as an object needed to be protected by the two male characters, Paul and Greg, who are trying to have sex with her. Ostensibly it is to save her life but they both have ulterior motives.

The idea that women are damaged goods after having sex and the idea that sex is a violent, predatory act has an obvious expression in this monster stalking Jay. She is also looked down upon by the neighbourhood and becomes the object of gossip.

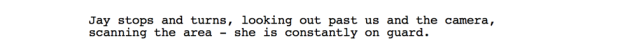

Also there’s the idea that women use their femininity to get what they want in the fact that Jay needs to have sex with someone to save her own life. It also explores the idea of women as guardian’s of their own virtue. Jay is forced to be suspicious of every passing person as each could be the monster. She’s unduly forced into paranoia and fear. She cannot afford to be caught off guard. These concepts are all touched upon but it never feels preachy. It is using the concept to comment not these ideas as being wrong or right but on how we perceive them and how male and female gender roles affect behaviour.

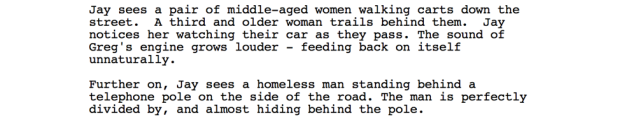

One feminist concept that the movie does clearly come out against is the idea of the male gaze. It appears constantly. Two neighbourhood boys constantly creep on Jay, trying to catch sight of her changing.

This starts out as relatively harmless but later evolves into homeless men and more threatening moments.

Also, Paul and Greg are also seen leering at Jay throughout. Paul is in love with Jay and Greg is a notorious playboy.

Both are looking to help ‘save’ Jay which removes her agency and both are doing it for selfish reasons. In the end she infects both of them. Greg is killed, and Paul passes the disease onto a sex worker but all that does is delay the inevitable. The movie takes a dim view of love. Jay has moved on from risky, manipulative bad boys, to Paul, who the end of the movie finds her dating. This move was partially out of necessity though as he was willing to take on the monster and the end of the movie finds them in danger. In the final scene that we see the monster, it is in the form of Jay’s father, staring at her. It is one of the only times the monster stands still and is a final expression of the dehumanizing male gaze.

As a feminist text, this screenplay makes effective thematic comment. Like a zombie movie, the concept of a shape-shifting sex monster allows a simple juxtaposition that can be used to comment on practically any concept (more on that later) but how does it function as a horror?

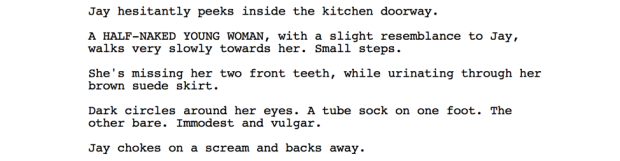

The script contains a lot of horror but it presents chilling moments in the simple, matter of fact way that it presents two people sitting, having a conversation.

This is counter to the typical approach of most supernatural horror which relies on elaborate special and practical effects and lighting. This script (and the film based on it) keeps the world grounded in reality as much as possible and this makes the scares that much more effective. The only supernatural element in the film is the monster and it takes the form as just any random person following the character. No elaborate makeup or scary demon face. This stripped back portrayal without huge set piece moments keeps the viewer/reader in the moment and allows tension to be slowly ramped up over the whole movie. There’s no warning to when the monster could arrive. And it makes any random person mentioned in the script a potential threat. Even characters we know could turn out to be the monster.

This normalization of horror is intensified by the use of commonplace and relatable settings: suburban streets, homes, a lakeside cabin, a high school. The world has a sort of Pleasantville, nostalgic quality to it but the slick, unpretentious dialogue dialogue and straight ahead portrayal of these characters prevents it from ever feeling twee or manipulative. These simple, safe settings are contrasted with the grime of Detroit: abandoned buildings and the dangerous 8 Mile area come at times in the piece when things get truly dire. This is a metaphor for the move from the innocence of childhood into the dangerous adult world, through the gateway that is sex.

When Jay is first given the monster, she moves from the safe nostalgic world of a quiet secluded spot in a vintage car into the nightmarish world of an abandoned warehouse where she is tied to a wheelchair. The next spot like this is “Hugh’s” squat. We find out that he really lives at home with his parents but after contracting the monster, he was forced to live in an abandoned house in order to remain anonymous as he tried to find a new partner to pass it along to. The final place is the abandoned pool, comes right after a monologue about the dangers of 8 mile. This place represents the synthesis of the two worlds, the synthesis of childhood and adulthood. The characters view it as a place where you come to hook up as teens. It’s abandoned but is falsely idyllic in that an abandoned pool wouldn’t be clean and well kept. It’s in a dangerous neighbourhood. It’s also where they take on the monster with a pretty harebrained, childish scheme involving throwing electrical appliances into a pool to try to electrocute it. In the end, their scheme fails and Paul bests the monster, (for now) shooting it in the head over Jay’s shoulder, almost killing her and injuring Yara in the process.

There’s a constant interplay between adulthood, childhood and teenagehood. They play childish games like “the trade game” and old maid and work at an ice cream stand but they also drink and have sex. Three of the characters are 17 but our lead is 19 and trying to make sense of being on the cusp of adulthood:

Also the creature’s torment infantilizes her and forces the younger characters into the role of caretaker.

In the end, Jay is forced to grow up and take control of her sexuality, deciding to only pass it to those she trusts rather than dooming a random person to death to potentially save her own skin. This simple sequence, in which Jay decides not to pass the monster to strangers, is Jay’s crystallizing moment that defines her as a character.

The secondary characters share this same formula. They’re archetypical but the situation forces them to rise above their station. Kelly, the kid sister, has to act as almost a parent to Jay, assuaging her fears and looking after her. Greg, the player, becomes a protector and his death, while not unselfish, comes in protection of Jay. Paul, the hopelessly in love younger guy, eventually gains Jay’s affections and has to make the difficult decision of whether or not to pass the monster onto a sex worker, something that the shy boy at the beginning of the movie would never have done. These characters are simple but drawn realistically and forced by their extreme situation to cope with it in a way that reveals hidden depths as all do when on the cusp of maturity.

In a sort of mirroring of this idea of being caught between different ages, the screenplay does a lot to play with time period. They watch old movies on tube TVs, they go to a movie theatre with an organist and their houses are decorated in 70s style. Two phones in the piece are described as “70s style” and “80s style”. Characters read pornographic magazines, a throwback. One of the most notable elements of this is Yara’s cellphone. It’s a pink shell compact that she reads ebooks off of the bulk of the movie. This was an element invented for the film and it looks equal parts antiquated, childish, and futuristic.

The monster’s final form is Jay’s father, a character never seen in the rest of the film and presumed to have either died or abandoned the family. This is thematically significant as it ties together the idea that sex is a life or death matter and has far reaching consequences. We are born from it and (in this world) it can kill us. The device of the monster changing forms allows strong thematic comment simply by the form chosen. The monster literally fucks its victims to death. The only time we see this in the movie is when Greg is killed by the monster in the form of his own mother. This is some obvious oedipal symbolism that doesn’t require a degree in philosophy to understand. This death scene makes us fear the worst when when the monster appears as Jay’s father and hammers home the idea that sex, parenthood, adulthood, and childhood are inextricably linked.

There are many other themes and techniques that this piece plays and I could write an entire essay merely on how it does dialogue, subtext, or poetic language but hopefully this will go a long way to convincing you that It Follows is one of the finest horror screenplays in modern cinema.