Happiness (1998)

Happiness (1998) is a film like no other. It’s a movie that I need time away from after each viewing, it’s effortlessly hilarious, and meticulously disturbing. It makes me laugh, and it makes me sick to my stomach, often simultaneously. It’s like an episode of Full House written and directed by Lars Von Trier. It’s a friendly nightmare.

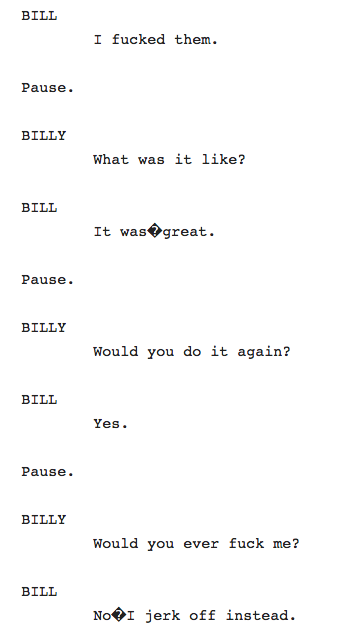

Writer/director Tod Solondz has wrapped a seething anger into a remarkably tight script. So tight in fact, that to someone who has not seen the finished product, the script comes off as very nearly lazy. Scene construction is very simple, settings are established with little more than the slugline, and conversations play out with very little action interspersed. This isn’t layover habits of a playwright-turned-screenwriter, nor is it laziness. The little action and description he gives is what turns up in the final film. Take this scene for example.

Slugline, who’s in the room, then a 3 minute monologue. We’ve never seen these characters or this setting before. It’s a level of economic writing that I haven’t seen from another writer. And what’s so impressive about his style is how literally it translates to the film. Scenes frequently begin with a close-up rather than an establishing shot. Bill’s office is essentially 4 green walls and two chairs. The simplicity and sparseness of the action translates directly into the screen. Besides the occasional “CLOSE ON,” the action is written without thought to the technical execution, and yet the film is shot exactly how it’s written. Take the dream sequence of Bill opening fire on an unsuspecting park for example.

That six line description translates to a full minute of screen time, and yet those six lines aren’t open for interpretation. It’s exactly what Solondz wants to show, nothing more, nothing less. I think it’s important to look at how this translated in production. The first shot is a single panning shot reveals the sunny, warm day, gay and straight couples, family picnics, beautiful sunbathers, and Bill on the hill. The first three lines all in one short, simple camera move.

The next shot, he pulls out a gun and shoots everyone.

After four shots of people being killed, we end with the bloodshed.

Six lines of action, seven shots. It’s written deadpan, it’s shot and edited deadpan. Tod Solondz delivers every scene–whether it’s a conversation, the premeditated assault of an 11-year-old, or a mass-shooting in the same vein. Only the music affects the deadpan execution of the often obscene content, and even then, it’s often cheery. It resembles a multi-cam sitcom at almost every turn, and it’s perfect. Any other sort of style would betray the authenticity of the world.

So we’ve covered the style. It’s simple, matter-of-fact, and uncaring of the gravity of the content. It’s anything but conventional. And while the seemingly randomly edited braided narrative may be just as unconventional, the story he tells doesn’t fall far from traditional structure. In fact, the arc of this 2+ hour nightmare may be the most conventional thing about it, and it provides a narrative through-line to this painful slice-of-life that Solondz has crafted.

The opening image flawlessly captures the central theme and tone of the piece as well as the struggle of our many protagonists. The tone is dry. The central theme is simple: don’t be honest. Honesty is the antagonist in this sweeping narrative, and the film begins with a relatively small-scale example of that. Though the word “honesty” was cut somewhere between the draft I got a hold of and the final cut, Joy is telling Andy that she doesn’t want to see him anymore. It’s Joy’s honesty that hurts Andy (named Stuart in this draft). By the end of the scene, Andy tries to hurt Joy, but he ends up projecting the way he feels about himself onto her, assuming the reasons he hates himself are the same reason she hates him. Look at this short example of honesty hurting Andy here.

It’s simple, dry, and cutting. But buried in this quick exchange is a seed that not only grows throughout the film, but is revisited at the end of the set-up. Joy’s honesty–that there wasn’t someone else, that she grew tired of Andy without anyone’s help–plays like a joke here, despite the clear damage it does to Andy. But in our last scene of the set-up, we meed Mona and Lenny. Another couple going through a breakup, only this time they’ve been together 60 years. In that scene, Mona asks the same question, though she says it as though she wishes for it to be true.

The real truth–that Lenny is in love with no one else and just “wants out” is so much more hurtful than being replaced. The rest of the set-up is ripe with examples. Allen rants to Bill about how he wants to have sex with (or most likely, sexually assault) his neighbour, and that honesty is repulsive to Bill. Bill is then honest about his mass-murder fantasy, and his therapist is turned off by it. Trish tells Joy that she never thought she’d amount to anything. The closest thing to a theme-stated comes from Bill, when he asks his wife (Trish) “what secrets would you like me to tell you?” Ironically enough, though the characters speak blunt and plain, one of the only things left un-stated is the stated-theme. The implication of Bill’s question is something along the lines of “you don’t want to know about my secrets.” This is punctuated a few scenes later, when Bill masturbates to a children’s magazine.

With it’s cast and arc-count so high, the film is inherently tangential and scattered, and that’s why Solondz’s commitment to the theme is so crucial. Everything these characters do stems from honesty. The catalyst here lies with each character deciding to be honest about their pursuit of happiness. The debate is whether that honesty’s consequences are worth it. Bill wants to have sex with kids. Joy wants to better herself through impulse, Lenny wants to be alone, Allen wants to form a connection of some of a connection with someone, Kristina wants the same, apparently with Allen, Hellen wants more life experience so she can be more honest in her writing. Billy just wants to come. Really badly, and he’ll ask his loving father for advice right up until he finds out what he is. Trish may in-fact be the only character unwilling to be honest with herself, and in the end, she isn’t punished or rewarded. The pursuits of these characters are noble, and relatable (save, of course, for Bill), but it’s in the inner truth of the characters that we see their ugliness.

Another layer of genius found in this script is Solondz’s refusal to judge any of his characters for their actions. The language of the action never changes, whether Joy is feeling good about her one-night-stand (a rare instance of consensual sex in the film) or Bill is drugging his whole family along with his victim, the script doesn’t judge. This translates into the film in one particularly compelling way: the soundtrack. The soundtrack in this film does something very unique. It doesn’t project any moral compass, it doesn’t play a theme that fits with what an audience interprets, but rather what the character is feeling. When Joy is riding on that post-coital glow, she gets a celebratory swelling string theme. When Bill sees his first victim for the first time, he gets a curious, playful little tune. The only other film I’ve seen that emulates this style would be Nightcrawler (2014). The difference being: Nightcrawler is a relatively easy subversion. Just play cool, hero music whenever Jake Gyllenhaal is doing something deplorable for his own gain. Happiness uses it’s theme as an extension of Solondz’s judgement-free writing. No character’s actions are presented any differently.

This choice ties into the film’s narrative. As we approach the midpoint, each character is rewarded for their honesty. Solondz’s universe answers their call. But in this cynical hellscape, the characters are now faced with a new challenge: whether what they thought they wanted was worth it. Consider this exchange, where Helen exclaims that she’s worthless because her writing is disingenuous. She writes about child rape, yet she was never raped as a child, and therefore she’s nothing. Meanwhile, Allen is continuing his compulsive harassment of Helen to make up for his inability to talk to her.

Hellen’s call is answered (ironically in the form of someone calling her).

Conversely, Allen’s call is answered as well. And yet right in the moment he gets what he thinks he wants, he realizes he is still unable to achieve it. His opening monologue tells us that he’s sure Helen would reciprocate his feelings if he could just tell her how he feels, and now that he’s told her the most ugly, honest way he feels about her, and she’s into it, he folds. This is Solondz’s greatest irony, an Inception of honesty. Beneath Allen’s honesty about his desires is a deeper truth: that he is unable to achieve it. And so goes for the rest of our cast. Joy leads her life in a way she thinks will help her. She leaves her call-centre job to teach and help people, even breaking a strike to do it, only to be heckled and ridiculed. She goes home with a man that seems genuine enough, and he steals her guitar. Even that character can’t be blamed in Solondz’s script. He tells her straight up: in Russia he was a thief. As with each segment of the film, the most effective tool is Bill. He got what he wanted, he was honest with himself and he assaulted a child. In the midpoint, he doubles down, and sneaks off to a child’s house after learning that he’s home alone.

On it’s own, what Solondz does with the character of Bill is a monumental achievement. Bill is the epicentre of what makes Happiness an incredible script– I sympathize with him. I understand that sentiment is largely subjective, but the fact that anyone can sympathize with him, the fact that Solondz can even justify Bill’s majority screen time is a rare and deeply challenging achievement. It stems from the choice that I’ve mentioned before: Solondz treats these characters with no judgement. They act from the same impulse. A spectrum of interpretations and pursuit of the ID. Each character has a want, and each character decides to be honest about it. Each character gets what they want, and most regret it (Lenny being the only exception). It’s this choice that creates an otherworldliness. This is where the sitcom aesthetic in the final cut comes from, and why it works. The depiction of each character, no matter their moral compass under the same naive, glowing lens creates an incredible sense of cognitive dissonance. I was rooting for Joy to find, well, joy. I was rooting for Lenny to find happiness in his lonesome, and for Mona to find happiness after his abandonment. I was rooting for Kristina when she pursued Allen, and I understood why she killed Pedro. And unfortunately, despite my own moral compass and every inch of my being knowing full well that Bill deserves the death penalty more than he deserves a second chance, I was rooting for him too. Not in the scenes when he actively attacked his victims, but in the spaces between. Seeing his pain, however deserved, was moving. Bill is an honest man. A deeply despicable one, but honest. And just when all sympathy for him once more disappears as he drives off to assault the child left alone in his house, a small shred of it comes back when he tells his half-awake wife a shred of truth about himself.

“I’m sick,” is one of two shreds of remorse that Bill shows in this film, and somehow it’s enough to keep me from seeing him as all-monster. In that segment too, is another strong device that Solondz uses to keep that cognitive dissonance alive: the punchline. Almost every scene ends with one, and no matter how disturbing, sad, or disarming the scene was before it, we always leave it with a laugh.

The ending of this film drives home the point that Solondz wanted to make all along: that there is none. Honesty isn’t a cure-all. It’s something that should be considered only occasionally. Joy stays honest to herself, and lends Vlad (her one-night stand) $1000 that she doesn’t have so he can pay his rent, only in exchange for what he stole from her. She loses. Allen tries to make his move on Helen in person, after she persists for days on end, and fails, only to have a tender moment in bed with Kristina. Despite knowing that she is a sex-repulsed murderer (albeit, in self-defence), he is able to connect to her. He sleeps above the sheets while she sleeps below, backs to each other. It’s the closest he’s gotten to a connection in the entire film. He wins. Lenny is vindicated in his desire to be alone, he wins. Finally, Bill gets what he deserves. Whether it’s an arrest, or vigilante justice, we’ll never know.

There are two final moments in the film that restate the theme and solidify its concept as being ultimately important. The first is the final scene with Bill, as he tells his son everything he’s done.

Easily one of the most disturbing conversations ever put on film, and yet I don’t see it as shock value, nor do I see it as exploitative. Bill tells his son, and the audience exactly what he is. We assume he will get punished for it after, and we know he deserves it. But there’s something tragic about it. “I couldn’t help myself” isn’t a good excuse for anything, but the honesty in his words are somehow heartbreaking. Solondz know what Bill is, and what we all think of Bill, but the last thing he does before withholding his fate is humanize him. He humanizes him almost as a fuck you. Like, before this monster goes down, you will look at him and feel a shred of sympathy. And again, I speak for myself, and admittedly, Dylan Baker’s performance in this scene has a ton to do with why I felt that way, but regardless of what a person has done, watching them dig their own grave with honesty alone is universally tragic.

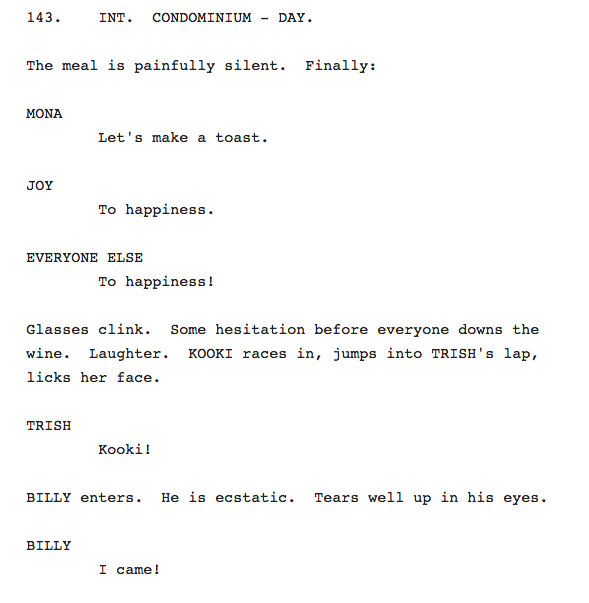

And then we get this:

For some context, that dog just got finished licking up Billy’s semen. It’s the last completed arc. From the very start, all Billy wanted to do was come. Like each scene, the film ends on a punchline, and this one is especially bitter. After everything we’ve seen, all the horrible acts of sexual violence and painful human interactions, Solondz throws it in our face (no pun intended). Because nothing matters. No matter how moral or honest you are, it’s a stupid joke. To me, ending Happiness with “I came” is like how Tarantino ended Inglorious Basterds with “this may just be my masterpiece.” It’s the perfect bow on this twisted gift.

I don’t expect anyone to like this movie, despite its critical acclaim. I don’t expect anyone to sympathize with Bill, either. But if you sit through Happiness, what you will be is challenged. It’s one of the most raw, honest films I’ve ever seen, and whether you agree with it’s message or not, whether you agree that in the scheme of things, an innocent pursuit of happiness can burn you just as much as preying on children can, you’ll at least be forced to consider it, and to make matters worse, you’ll be laughing the whole time. That is what makes this script so incredible.